Osteoarthritis: painful joints

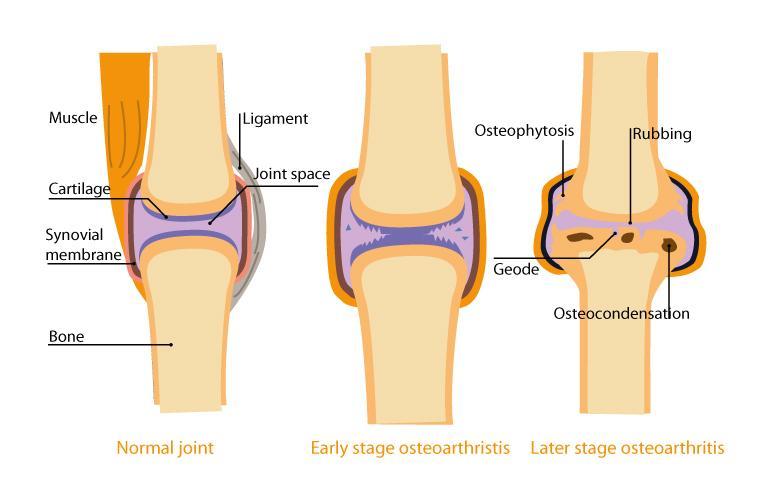

Osteoarthritis is a condition which affects the joints and occurs when the cartilage which protects the joint loses its smooth appearance as micro-cracks form and cartilaginous debris builds up in the joint.

The joint space reduces and the ends of the bone rub against each other. Evidence of joint degradation may then appear:

- osteophytosis (the formation of bone spurs)

- geodes (abnormal cavities in the bone)

- osteocondensation (bone density increases and the bone becomes more brittle)

These lesions can, in some cases, cause great discomfort and pain on a daily basis, resulting in a loss of mobility.

Osteoarthritis: the numbers speak for themselves

- Almost 10 million French people suffer from a degree of osteoarthritis1 that impairs simple movements2,

- Osteoarthritis affects just 3% of people under-45 year olds, but in the over-65s group, 65% of the population is affected, with this figure increasing to 80% for the over-80s1,

- In France alone, osteoarthritis generates 9 million medical consultations a year, 14 million prescriptions and 300,000 radiological examinations3. For this reason, it is now considered to be a significant public health issue in France.

Risk factors for osteoarthritis

A number of factors affect the age of onset of osteoarthritis and the initial expression, i.e. a break down of the cartilage, is very commonly seen in individuals between 50 and 60 years old. This pathological process, which is generally age-related, may also be due to:

- metabolic malfunction conditions (obesity, diabetes, etc.)

- overloaded joints (excess weight, frequent carrying of heavy loads, over-intense physical exercise1, etc.)

- the expression of particular diseases in joints

- intrinsic weakness of the cartilage.

Family history is a risk factor in certain cases, notably for osteoarthritis of the hands.

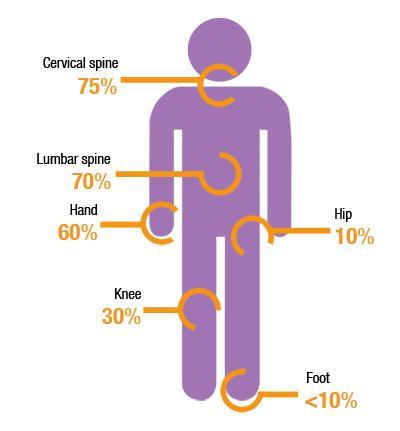

Osteoarthritis: the joints affected

In the 65-75 age group, osteoarthritis affects:

- the spine (70 to 75 % of cases),

- the fingers (60 %) one of the notable consequences of which is irreversible deformation,

- knees and hips (30 % and 10 % respectively).

Osteoarthritis of the knees and hips is the most disabling since it limits mobility. All the other joints may be affected, although the shoulder, elbow, wrist and ankle are more rarely affected1.

A closer look at cartilage: the joint’s shock absorber

Cartilage is a living tissue which covers the surfaces of the bone and thus allows them to slide over each other.

- With a water content of 70 %, cartilage is rigid yet deformable so that it can absorb impacts of all types.

- It contains neither blood vessels nor nerve endings and is a structure made up just one type of cell: chondrocytes, which lets cartilage renew itself continually, even in older adults.

- It also contains collagen fibres and proteoglycans. The latter improves the elasticity of the cartilage.

During the osteoarthritis process, an imbalance between the rates of chondrocyte synthesis and degradation develops in an inflammatory environment which causes pain and often produces acid, which aggravates the lesions of the cartilage.

Unpredictable progression

Lesions of the cartilage do not resolve with time, and neither is their progression linear. The degradation can occur very quickly, with a prosthesis required in some cases in less than 5 years (e.g. for osteoarthritis of the hip). In contrast, the degradation can advance very slowly, over many years, without causing any significant disability4.

Osteoarthritis typically progresses by alternating between two phases, with the duration of both being unpredictable:

Chronic phases

The daily levels of discomfort vary and the pain is moderate.

Episodes of acute pain

These episodes are accompanied by inflammation of the joint: the pain is intense.

Treatment for osteoarthritis

In the large majority of cases, the patient is offered a drug-based treatment combined with a non-pharmacological therapy to alleviate the symptoms. This involves reducing the pain and the disability.

Drug-based treatment

- Analgesics may be prescribed to relieve the pain (paracetamol or anti-inflammatories for inflammatory episodes).

- When the pain is not relieved by analgesics, corticosteroid infiltration therapy may be administered (whereby powerful anti-inflammatories are injected into the joint).

Non-pharmacological therapy

- This therapy is primarily based on improving health and making changes to diet: the overall aims are to lose weight and take physical exercise during the chronic phase of the condition.

- From a nutritional perspective, omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, are known to have anti-inflammatory properties4,5 and can be beneficial.

Limiting pain without the use of medicines

Chondroitin sulphate and glucosamine sulphate

Two natural substances have been the subject of a number of placebo-controlled studies: chondroitin sulphate and glucosamine sulphate. EULAR (the European League Against Rheumatism) recognises their beneficial effects in relieving the symptoms of osteoarthritis6. Glucosamine sulphate and chondroitin sulphate are very similar to two substances naturally present in cartilage. Moreover, they do not simply relieve the symptoms; they might also contribute towards slowing the progression of the disease, without inducing side effects. The two compounds appear to be synergistic, i.e. taking them together strengthens their actions7.

Plants that combat inflammation

Devil's claw9, willow10, turmeric and boswellia all have anti-inflammatory properties. Studies have particularly demonstrated the benefits offered by turmeric11 and boswellia12 in reducing joint pain in patients with osteoarthritis.

Fitting a prosthesis

In cases of severe disability, fitting a prosthesis may be considered with a view to restoring mobility to the damaged joint. Surgery (“arthroplasty”) is primarily performed on the hip and knee, and much more rarely on the shoulder.

During the procedure, the diseased joint is removed and a prosthesis (artificial joint) fitted in its place. Although it significantly improves quality of life, its efficacy is nonetheless time-limited to about ten years on average.

What you can do to preserve your joints

To limit the progression of osteoarthritis, it is advisable to13:

- Take regular physical exercise, but not during inflammatory episodes, lasting for one hour, three times a week to maintain the mobility of the joint and strengthen the muscles: walking, swimming, cycling, gentle gymnastics.

- Lose weight if you are overweight (all excess weight is an added burden for a painful joint) and avoid carrying heavy loads,

- Adapt your environment to your state of health: for example, bath access ramps, a walking stick used during inflammatory episodes or store utensils within each reach in the kitchen.